Designing a DAW in the age of AI

Bronze’s Lex Dromgoole on the quest for creative parsimony

Hello – after last week’s shock(ish) news about Pioneer DJ and Serato dropping last minute, we’re back on track. I’ve always wanted to dive deeper into the DAW and its cultural impact on how music sounds in 2023. I think a lot of people point to distribution and streaming platforms as why music feels homogenised, but the tools we use get a free pass. I think there’s a story there for sure and it’s something I’ll be exploring in a bigger piece later in the year. For now, enjoy this chat with Lex, a little teaser of what’s to come. As always, thank you so much for your support.

Declan x

The Week in AI

WIRED has published a piece about the risks around AI and the atom bomb, I assume to piggyback the Oppenheimer hype. Apocalypse, now?

A company called The Simulation has released a preview of a new platform that allows you to create a whole episode of a TV show based on a prompt alone. They demoed it using a model trained on South Park. I genuinely can’t tell if this is a joke or not, but if it’s real then it feels like we’ve jumped another five years ahead overnight. Decide for yourself here.

AI music generation platform Mubert says its users have created 100 million tracks so far. It’s largely designed to create music for short-form videos, podcasts, etc and they say their model is trained on licensed music.

AI plugin company Neutone has split off from its parent group to form its own company, starting with the release of Neutone 1.4. It’s capable of real-time input modelling, including models of Bulgarian choirs and Buddhist chants. Very crazy sounds, download it for free here.

Designing the future

One of the big challenges with any new creative technology is how it should feel in use. That might sound trivial but design decisions fundamentally define how we interact with tools. Good decisions can lead us seamlessly down unique creative paths, transcending the interface, and letting our imaginations dictate our actions, while bad ones can stunt our creative flow and blunt our inspiration.

For me, ChatGPT, and to a lesser extent DALL-E 2, didn’t torpedo AI into mainstream consciousness because of the technology behind them. They did so because of their interfaces. By creating the simplest possible UX and UI, every user who’s ever written an email, a WhatsApp message or conducted a Google search could immediately understand how it worked, at first glance. If it was solely about technological progress, that explosion would have happened when GPT-3 launched in June 2020. It didn’t exactly go under the radar either – the New York Times wrote about it at the time. What changed was how it was presented. Harnessing the power of billions of data points and trillions of potential outcomes into a single text box is what made ChatGPT the ‘game-changer’ that it’s become.

I believe this is the pertinent challenge going forward for UI and UX designers, especially when it comes to creative tools, music-making and AI. How do you design something that allows users to tap into an almost infinite number of potential creative outcomes, without overwhelming them with options? Where’s the tradeoff between presenting complexity as simplicity, without leading every user down the same creative path?

The Bronze age

These are the questions I explored with Lex Dromgoole, CEO of Bronze. Dromgoole’s background is in audio engineering, having worked with the likes of Björk, Arcade Fire, Madonna and many more while at London’s legendary Olympic Studios.

Bronze is a software platform that allows users to create AI models of their music, trained on stems or other audio inputs. Every time a user presses play, a new iteration of that song is heard, as if it’s being ‘performed’ in real time by the AI and ML tech behind the platform. The song will never be the same – every time you press play, a new instance of the track is generated based on the artists’ stipulations. The company have collaborated with Arca, Jai Paul, Richie Hawtin and more recently Disclosure, who used Bronze to create an endlessly varied version of their album ‘Settle’ for its 10th anniversary.

Bronze isn’t trying to replace Spotify, nor is it claiming that in the future every song we listen to will be a generative inference of music we know and love. The team has designed an API that can plug into other industries, from game developers to movie soundtracks and theatre work, art installations and more – introducing a new concept that ‘recorded’ music can at once be familiar and new. I wanted to find out more about how Bronze worked and how Dromgoole felt the DAW could change over the next decade as generative AI comes to dominate creative industries.

We also dove head-first into a wider topic around traditional DAWs, their limitations, how their design can stifle creativity and the challenges around designing a new creative tool that echoes the DAW concepts but with the limitless power of AI at its core. There’s also a little bit about the quest for precision in music, which I found fascinating.

Our conversation was part of a bigger feature on the future of DAWs I’m writing for another publication (coming soon, it’s a big topic!) but I wanted to use some of our chat here – it’s always thought-provoking to talk to Lex and what they’re building at Bronze never ceases to blow my mind every time we speak. This gets pretty dense pretty fast, but I hope it’s some food for thought about how the future of music-making tools might look, feel and sound.

FF: What exactly is Bronze?

Lex Dromgoole: “We’re creating a system that allows people to make and release music that has all of the qualities of recorded music and many of the qualities of performance when experienced by a listener. This means that the compositional process in Bronze is not a static piece of music, it’s much more of a holistic representation of that music.

“The way you can imagine this system working is, you create a piece of music in the DAW and rather than rendering it out as a static file, what you’re rendering out is a model of a performance, with all of its constituent parts. At the moment those constituent parts are mostly recorded audio, but what we imagine in the future is actually deep learning models for audio resynthesis, nested within bigger and broader models for structure.

“As someone who cares a lot about music production, I don’t think we’re going to want to cede all of our creative control to more broad brushstroke models. I think we’re going to want more distinct, more defined models that we can use for certain things within our production, and we’re going to want to arrange those in certain ways. It’s more of a hybrid way of thinking about these tools.”

How do you view the impact of generative AI tools, in general, from the perspective of music makers?

“When it comes to AI and the concept of things being generative, it’s different for music. Music historically has always been experienced ‘generatively’. There’s a whole 45,000 years of history where we only experienced music as a performance. Recorded music initially was creating a document of performance – one particular performance – and it was brilliant at that. When we moved beyond that into constructed music where we could create composite performances and remove that temporal boundary of recorded music being a document [of one moment in a studio or stage], it stifled the process in a way.

“Music is very different from something like film. Film is just film, it happens in a particular chronology. Music isn’t like that, there can be many brilliant performances of a piece of music that are all true to that piece, and that’s how we’ve experienced it for the biggest part of history.

“In terms of tools, AI can come into it in many different ways. Obviously, we have [Google’s] MusicLM, or any automatic content creation system which is essentially some kind of prompt. That’s good for certain circumstances and applications, but our particular path is to do something where you can be much more precise about those outcomes, and you can use them nested within something you have more autonomy over shaping.”

“Music historically has always been experienced ‘generatively’. There’s a whole 45,000 years of history where we only experienced music as a performance.”

What kind of examples are you thinking of when you say that?

“In musical terms, you could imagine the qualities of a particular sound could be an inference, or a model, rather than a recording. That could be having a region on a timeline that’s a resynthesis algorithm. And in order to do that you need to train things on your own sounds – that’s a very important part of what we’re going to see in the future. The ability to train models directly within a DAW. We don’t have any pre-trained models in Bronze. The deep learning, resynthesis aspect could be anything from a sound, to a musical phrase, to maybe a passage, but it would always be more granular elements of your composition.”

And this would still be within a traditional arrange view?

“Yes directly within a traditional arrange view, although one of the things we’ve been developing is the idea of, rather than having a linear timeline, we have a dynamic timeline. It’s a timeline that’s more like a canvas or a palette where different possibilities can happen in real-time. So it’s a hybrid system between the linear, left-to-right view that we’re all accustomed to – you’re not really able to abandon the fact that time moves from one side to the other. We’ve tried many, many times.” [Laughs]

I feel like the arrange view in a DAW is responsible for a lot of creative block. For example, if you sit down on your sofa and pick up a guitar, you strum it for 20 or 30 minutes, you noodle around and you don’t play any particular song and you certainly don’t record it. You put it down and that’s it – you’ve expressed yourself creatively, you’ve enjoyed playing the instrument and you never even considered what that process was ‘for’.

In a DAW, we are immediately presented with a timeline that constantly suggests ‘What’s next?’ You have these markers for eight bars, 16 bars, 32 bars – every time you create an idea the onus is to then move forward. ‘Where are you going with this? Who is this for? Where is it for?’ If it’s for DJs to play it’ll need breakdowns, if it’s for the radio it’ll need to hit the chorus quickly, etc. The timeline in a DAW very quickly makes the creative process a very functional one – and I think that pressure to create something tangible every time you open the DAW is what makes people go into a building-blocks mode instead of staying creative, and by doing that, they get stuck in loops.

I’d love to see a solution to that problem, and I know you said you’ve tried – I’m not surprised you haven’t been able to solve it.

“The way I think of a timeline is that it displays the temporal extension of music. The extension of music across time. Because we have a dynamic timeline that can manifest in many ways, Bronze has temporal depth. It’s almost like a three-dimensional layering of a timeline. It doesn’t look like that, but it manifests as that.

“Interestingly, going back to your point about the guitar, in almost every philosophical tradition, they have two different notions of time, one which is time as measured, and one that’s time as experienced. We know that the time we experience is not the same as time as measured. I would argue that one of the things that DAW design has imposed upon us is a very stripped, arbitrary notion of time. The grid is our north star for everything and I think that’s a significant problem for many reasons. That’s not how we experience time when we perform music, or when we listen to it.”

The MIDI piano roll kind of falls into the same category. I hate that little pencil.

“That’s another great example of imposing a particular framework on a user interface that makes us subscribe to an equal-tempered, Western version of tuning when there are many different ways that that can manifest. This is why when Aphex Twin makes records and makes micro-tonal scales of his own, they sound interesting and compelling to us even though we can’t tell why.

“One of the things we’ve travelled further towards is this pursuit of precision. Almost everything that’s perceived as being an innovation [in a DAW or plugin] is a route to something that’s more of a precise representation of music. Actually, I think we need to move away from that. What we need are tools that provide us with inspiration, serendipity, and unexpected consequences. With the ability to make and structure music in a way that feels more performed and more living, than constructed.”

“Almost everything that’s perceived as being an innovation [in a DAW or plugin] is a route to something that’s more of a precise representation of music. Actually, I think we need to move away from that.”

How do you marry your philosophical approach around UX and UI without alienating your potential user base?

“That’s the million-dollar question. How do we move from this current paradigm of music production, into a space where it feels more like the kinds of things I’m describing? I don’t think you can abandon a lot of the things that we already have wholesale, but I do think there are a lot of things you can do differently.

“If you look at the iPhone, it’s the perfect example of conceptual parsimony. The main consideration, apart from the quality of the interface, is that it’s conceptually simple. At the root of all great UX and UI design, that’s the north star. But, when the other consideration is that there’s going to be a creative outcome, you have a huge responsibility to ensure that [the design] doesn’t make everyone make the same creative decision.

“I think the main reason the piano is the most ubiquitous instrument is that it’s the most conceptually simple, but you can spend the rest of your life exploring the nuances of it through performance. Interestingly, far more complicated instruments like the clarinet are conceptually much more difficult – and again, you can spend the rest of your life exploring the nuances in terms of the tone and timbre, etc – but I would say there’s a reason the clarinet has not endured the way the piano has. And I think we need to take the same approach when designing instruments for arranging and creating music.

“I feel like we’ve sleepwalked into this situation where musicians are expected to engineer and produce and create music on their own, but the fundamental principles of the tools they’re using to do that were only ever designed to be used by engineers. And then software engineers were the people tasked to make them more intuitive and more accessible to musicians, not musicians. I think that’s a significant reason why some people feel limited by these tools.”

“I feel like we’ve sleepwalked into this situation where musicians are expected to engineer and produce and create music on their own, but the fundamental principles of the tools they’re using to do that were only ever designed to be used by engineers”

How does that affect creativity, do you think?

“If you create a tool that’s designed to be used by technicians, it makes you pay a very particular type of attention to music, right? It pushes you into a type of attention concerned with the technicalities, with precision – the kind of things we’re seeing in modern music. A lot of music, in terms of the way it’s constructed and the way it sounds, tends towards homogeny. I think it's because the tools we're using were originally designed for engineers. I don’t think that type of technical attention is the same type of attention you pay when you’re being creative.”

This reminds me of the analogue versus digital debate – precision versus ‘character’ and other more nebulous terms.

“[The analogue versus digital debate has] always been focussed on sound quality and it’s never been about that for me. It’s about the type of attention you pay when you use physical objects.

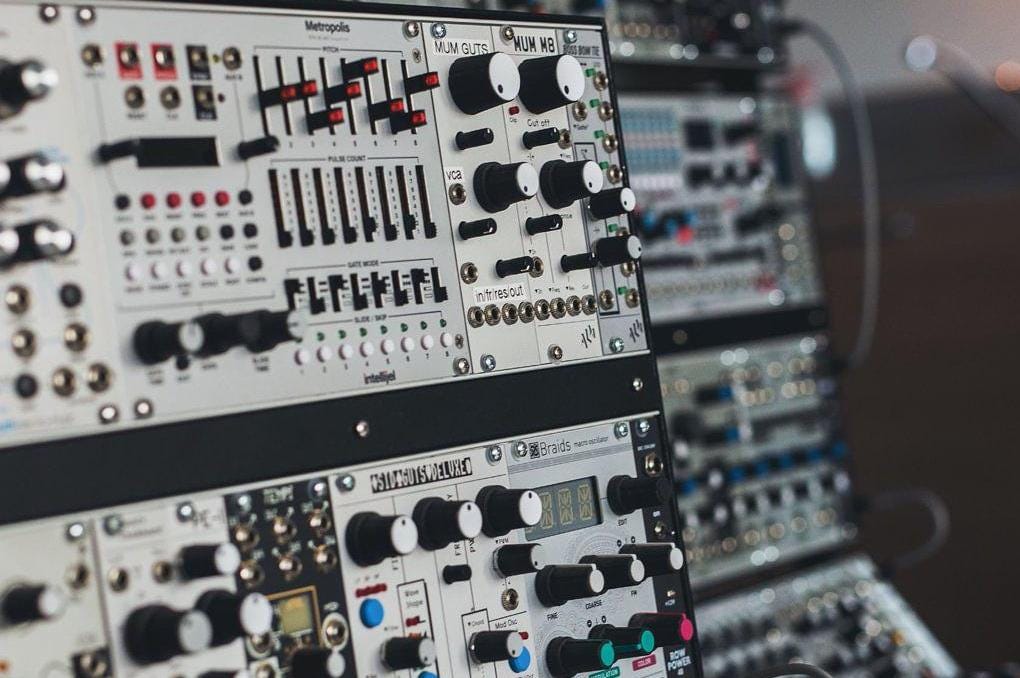

“In my studio, if I use the modular [synth] and then go through the [Neve] 1272s, then through a particular EQ or compressor on the desk. Chances are no one’s used that exact chain before in that way. It’s a very subtle thing, but I can guarantee you almost everything I load up in Logic, someone else is using that chain because it’s in the computer and it’s designed to be part of a precise environment.”

Speaking of signal paths, will there be an element of machine learning in the mixing process with Bronze? Or is it purely around composition and structure?

“I’ve been saying this for a long time – I think interactive machine learning is being slept on across the board. Think about our interactions with a DAW and how many different things we interact with even in the space of an hour. The amount of information you could potentially learn from. Even in the most simple example – why when I’m dragging a piece of audio onto the timeline am I still having to name an audio track? It should know what that audio is and name it for me.”

If the DAW was always listening to you and learning your behaviours it may just suggest what you’ve done in the past. It might say ‘Last time you did this, wanna do it again?’ Some of that might be fine, if it’s just mix admin stuff, like rolling off everything below 20Hz. But where’s the line when you’re deciding how much you want the machine to do for you?

“I think you have to be very careful, that you don’t make everyone make the same decisions, and in the case of the individual, don’t make that same person make the same decisions [Laughs]. That’s part of where we’ve got to with this preset culture. There are so many interesting things that you can do from [machine learning inside a DAW] – if there’s a particular part of audio I really like, and I want to find all the variations of that, why do I have to drag in audio files and edit them? Why can’t I find all those variations automatically and create a model of them? If you’d recorded 10 minutes of your modular doing something, why can’t that exist as a model of your modular, instead of a 10-minute recording?

“I believe that the root of everything we care about in music is the relationship between things, not the things themselves. Everyone who makes music knows this. If you take one part out suddenly it falls apart. It’s because you’ve lost part of the relationship, not because you’ve lost a particular thing. Most of how we’ve designed these systems and how we think about music when we make it now is this idea of atomised things or components. What we really care about is the emergent quality of them when they’re together. What Bronze allows you to do is explore more of those in interesting ways, and actually in happenstance because it exists in improvisation.

“Beyond that, I think we might be able to move past a lot of the things that are the sticking points creatively because the system becomes so advanced that it knows a lot more about these relationships, rather than just thinking of different bits and pieces that have no correlation between each other.”

How do you see DAWs evolving with all of this in mind?

“I think they’re gonna have to adapt or die, to be honest. I just think that once you experience the products of these types of systems and how they feel musically, you can’t really go back. I’m not talking about Bronze specifically just anyone who’s working in this field.”

This interview was edited for length and structure. Bronze is entering public beta soon. Find out more on their website.

Other recommended stuff from the internet

The excellent Substack and music community Love Will Save the Day has launched a radio station, which starts broadcasting Saturday, July 22nd.

DJ Deeon – legendary ghetto house producer – has sadly passed away after a long illness. By all accounts one of the kindest people in electronic music. RIP.

Korg has unveiled a VR version of their plugin suite Gadget. It’s basically a virtual studio, with all the annoying parts of a real studio intact! I’d have much preferred to see a whole new interface concept, rather than re-creating a MIDI piano roll in a headset, but I understand too that you can’t go fully conceptual from the off. Hopefully it’s a success and we can see some more VR music-making tools.